China’s current ambivalent approach to the war in Ukraine may fit into an impression of strategic and rational behavior. While Beijing claims to respect Russia’s interests and trumpets President Vladimir Putin’s propaganda, it refuses to provide material support for the war and attempts to maintain relations with the European Union and the United States. However, there is a fairly strong likelihood that the Chinese leadership will become more and more irrational in the years ahead.

Several of the factor that led Putin to invade Ukraine are increasingly present in China. Putin believes that after the Cold War, the West brought Russia to its knees. By invading Ukraine, he is “correcting injustices” and returning Russia to its “rightful” position. The decisive factor here is the leader’s subjective perception, not the objective state of affairs.

As history has repeatedly revealed, a country’s feeling of being disrespected by other countries can lead to an urge to re-establish its position through conflict. An analysis conducted by the political scientist Richard Ned Lebow showed that of almost 100 international conflicts involving great or aspiring rising powers since 1648, international standing served as a primary or secondary motive for two-thirds of the wars, a much higher percentage than security and material interests.

China’s leaders have repeatedly made it clear that they feel the current international order is dominated by the United States, and that China’s international position does not reflect its actual power. Chinese propaganda builds on grievances toward the “foreign powers” (primarily the U.S. and Europe) that date back to the Opium Wars and the “century of humiliation.”

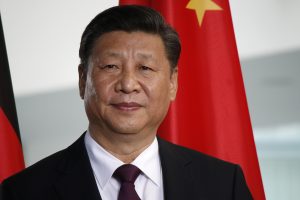

Under Xi’s leadership, increasing attention has been paid to national pride and China’s international standing in the official discourse. Since he came to power, Xi has been promoting a plan of “national rejuvenation,” which includes “unification” with Taiwan. During his speech to the 20th Party Congress in October 2022, Xi repeated his aim to accomplish unification by 2049.

Since the use of force against Taiwan is a red line for the United States, Xi may decide to cross it to prove that the “foreign powers” are not in a position to “dictate” anything to China anymore. As Lebow wrote in “A Cultural Theory of International Relations,” a leader who believes that his or her country is treated unfairly may perceive compliance as weakness that invites new demands, making a confrontational response more attractive – even if it is risky or costly.

Similar to Russian propaganda, Chinese propaganda has encouraged nationalist moods, which motivate demands for a more aggressive approach. Radical Chinese commentators already criticized Xi for not shooting down the plane of the then-speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, Nancy Pelosi, during her visit to Taiwan in August 2022, and they have increasingly called for a large-scale invasion of the island.

The urge to enhance international standing is closely related to the search for alternative sources of internal legitimacy. During his long leadership, Putin was not successful in implementing reforms that would increase economic productivity, forcing him to seek other rationales for his continued rule. Putin’s very election as president stemmed from the popular support he gained during Russia’s military invasion of Chechnya. Fourteen years later, when Putin decided to invade Crimea, it was shortly after large-scale political protests following his return to the presidency for a third term.

For several decades, China has been successful in increasing the living standard for the majority of its citizens and thus ensuring the government’s performance-based legitimacy. However, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is increasingly facing new challenges. The real estate market is an inflated bubble that will inevitably burst one day. To strengthen CCP control, Xi Jinping has been stifling major private firms, including the important IT sector.

In addition, China’s long-term zero COVID policy has significantly weakened the domestic economy and international trade. The government’s obsessive insistence on zero COVID led to a number of absurd situations, including a lockdown preventing Chengdu citizens from leaving their homes during an earthquake and extreme food shortages, which supposedly led to several deaths of hunger.

After the seemingly endless zero COVID measures led to widespread popular protests, China’s leadership pivoted and suddenly abandoned the policy. While the official statistics are downplaying the reality, numbers of COVID-19 cases and related deaths have skyrocketed since then. China’s people now face low vaccination rates of vulnerable groups, the uncertain effectiveness of domestic vaccines, overcrowded hospitals, and a lack of safe medicines – all amid a dearth of credible information. The ongoing crisis may deepen distrust in institutions and delay the Chinese economy’s recovery.

To support businesses, the administration has already pledged to give a larger space to the private sector and encouraged foreign investments. However, it is likely that Xi’s emphasis on centralization of power will eventually prevail, and that this will suppress free enterprise and innovation again. The absence of effective solutions could potentially urge the leadership to seek alternative sources of legitimacy, including through military means.

An increasing concentration of power within the hands of one individual decreases the quality of decision-making. When no one is there to challenge and reverse poor decisions, the consequences could be tragic. Two extreme examples of this are the brutal eras of Stalin and Mao. Unlike Mao, Xi maintains a well-educated and qualified bureaucratic apparatus and still appears to listen to moderate voices. However, the anti-corruption campaign and ongoing purges of cadres have reinforced fear among elites and reduced the likelihood of critical feedback. Plus, as the pandemic revealed, Xi already tends to react impulsively.

A growing unrest within the CCP related to his continuously tightening grip may increase Xi’s paranoia and trigger a purge of educated officials, which would be the first step toward a disaster. It is uncertain how much credible information still reaches Xi. However, even if he has an accurate picture of reality, with the growing concentration of power in his hands, it will be increasingly difficult for him to decide rationally when fulfilling his visions.

And as with Putin, Xi’s appetite to achieve “historical” goals such as the conquest of the claimed territories may grow together with his age.